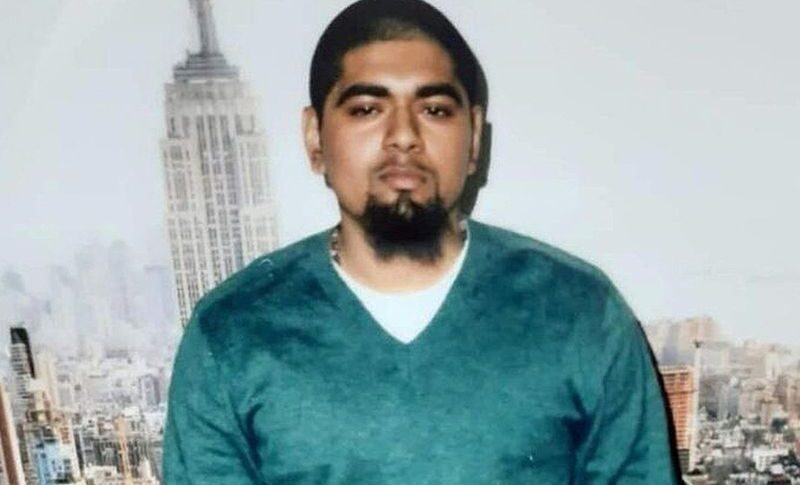

The Persecution of Guyanese Immigrant With Learning Disability Prakash Churaman, Mother Forced Confession because She Was Late For Work

Guyanese immigrant Prakash Churaman was 15 years old when police officers snatched him from his mother’s basement apartment and took him to the 113th Precinct in Jamaica, Queens. Without a lawyer present, Detectives Daniel Gallagher and Barry Brown alternately berated and cajoled Churaman for almost three hours. At the time, Churaman was taking anti-depression and anxiety medication and has since been diagnosed with a learning disability.

Although his mother was present, she didn’t understand the consequences of a confession and begged Churaman to cooperate with the police so that she wouldn’t be late for her job. Churaman finally confessed to being present at the scene of a botched robbery. Unknown to Churaman, Taquane Clark had been killed during that robbery.

He recanted afterward, but it was too late. Churaman was charged with murder — felony murder for participating in a felony, attempted robbery in Churaman’s case, where someone was killed — and didn’t come home for six years. He is still fighting the case to this day.

That Churaman would at first confess to a crime he now claims he didn’t commit isn’t shocking. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 22% of people accused of homicide gave false confessions. That figure skyrockets when the accused is a juvenile. Indeed, children are almost four times as likely as adults to confess to crimes they didn’t commit.

Even more overwhelming is that 70% of exonerees with a mental illness or intellectual disability have falsely confessed. Considering his age, learning disability and medicated status, it is reasonable enough to believe that Churaman simply said whatever he thought Gallagher and Brown wanted to hear.

Along with his recanted confession, the case also hinged on earwitness testimony of then-74-year-old Olive Legister. No, that’s not a typo: Legister isn’t an eyewitness, she’s an earwitness. She says she heard Prakash’s voice during the crime. Outside of Churaman’s recanted juvenile confession, Legister’s voice identification is the key piece of evidence linking him to the crime. There is no forensic evidence — fingerprints, DNA, video or murder weapon — that place Churaman at the crime scene.

For years, Churaman languished behind bars as he waited for a trial. A child living among men, Churaman suffered through anxiety and depression while navigating Rikers Island’s infamously violent and unsanitary conditions. During that time, he attempted suicide twice.

On Dec. 13, 2018, four years after he was taken from that basement apartment, Churaman, now an adult in the eyes of the law, was convicted of murder in the second degree. Almost two years later, an appellate court overturned the verdict because Churaman had been precluded from presenting evidence about false confessions.

Faced with a retrial, Queens District Attorney Melinda Katz offered Churaman a deal: plead guilty to assault and, with time served, be set free in weeks. Churaman, who maintains his innocence, rejected the offer, saying he refuses to admit to a crime he did not commit.

A child growing up at Rikers Island isn’t unprecedented. The name Kalief Browder reminds us of that. Nor is it surprising that a Guyanese immigrant like Churaman has struggled to navigate our criminal justice system. Guyanese in New York are both underserved and overpoliced.